Let’s resume what we know from the atoms: atoms can be broken and are composed of charged species – protons and electrons – and neutral particles – the neutrons. Atoms are different for each element (or isotope) by the number of those three species. A nucleus is at the centre of the atom and is surrounded by void and a cloud of electrons. The nucleus is made of neutrons and protons and makes the major part of the mass of the atom. However, the spatial distribution of the electrons is not random. Several planetary orbit theories were proposed after the works of Rutherford on the atomic nucleus but it is the Bohr’s model which can be considered as the first viable model. Some of the hypotheses of this model were not correct but it was the first step toward the understanding of the structure of an atom.

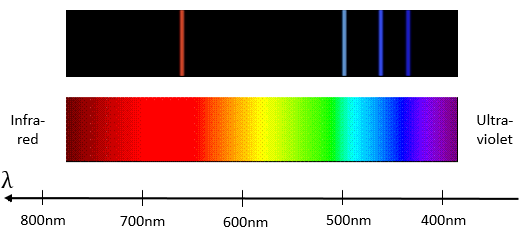

Bohr worked on the emission of light from dihydrogen H2. In an electric environment H2 dissociates in 2 excited H* that emit light to get back to its fundamental level.

hν is the usual way to represent a photon, emitted or absorbed during a physical or chemical process. h=6.626×10−34Js is the Planck constant. The emitted light has only a few selected wavelengths.

Based on that fact, he elaborated a model for the electronic structure of the atom. Unfortunately, the model only works for the Hydrogen and for the cation of He, i.e. atoms with a single electron.

Bohr used 4 postulates:

- electrons revolve on circular orbitals

- On a given orbital, an electron does not lose energy

- Gains or losses of energy correspond to the jump from one orbital to another one.

- Electrons are subject to a angular moment L

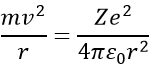

Bohr calculated the radius and the energy of the orbitals: to stay on a given circular orbital, the electron endures a centrifugal force (left part of the equation), which is counterbalanced by the attraction of the nucleus (right part)

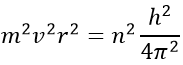

where ε0 is the permittivity of the medium. As mvr=nħ, we can simplify the equations from the square of it:

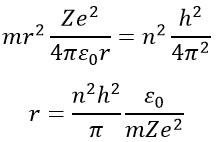

Injecting the centrifugal force into the previous equation, we obtain an expression for the radius of an electron:

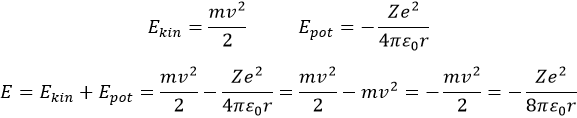

The energy of an electron is the sum of its kinetic energy and its potential energy. The potential energy comes directly from the Coulomb’s Force (remember that an energy is a force multiplied by a distance)

The radius was determined previously and can be used to determine the energy of an electron for a given atom

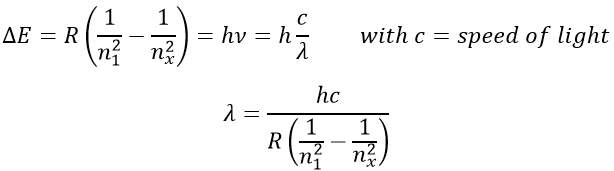

R is the constant of Rydberg and R=-2.178 10-18J.

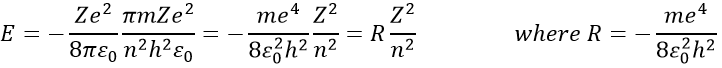

To jump to an orbital of greater number/radius, an electron requires a given amount of energy, obtained from heat or light. Doing so, the electron is said excited.

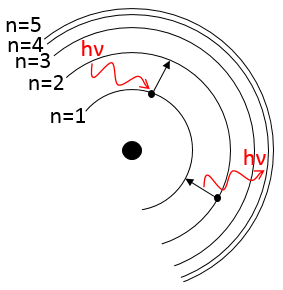

To go back to its fundamental state, the excited electron frees the same energy in the form of a light of a given wavelength. The wavelength of the light is directly related to the difference of energy between the orbitals:

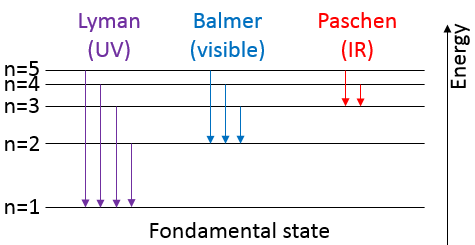

This kind of transition, from an excited level to the fundamental one is called a Lyman transition and emits in the UV wavelengths. If the destination level is not the fundamental one, others names are given:

The second hypothesis of Bohr was incorrect and electrons interact together.

To determine the correct form of orbital and the position of electrons, it is first necessary to develop quantum mechanics.

Quantum mechanics

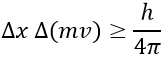

An important principle of the quantum mechanics is the uncertainty principle of Heisenberg: it is impossible to determine at the same time the exact position and the exact movement of a particle such as an electron or a photon:

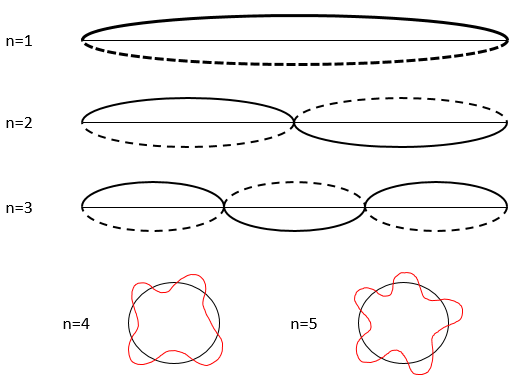

This relation means that we can only work with probabilities for an electron to be at a position. The electron is not considered as a point but as a stationary wave along its orbital.

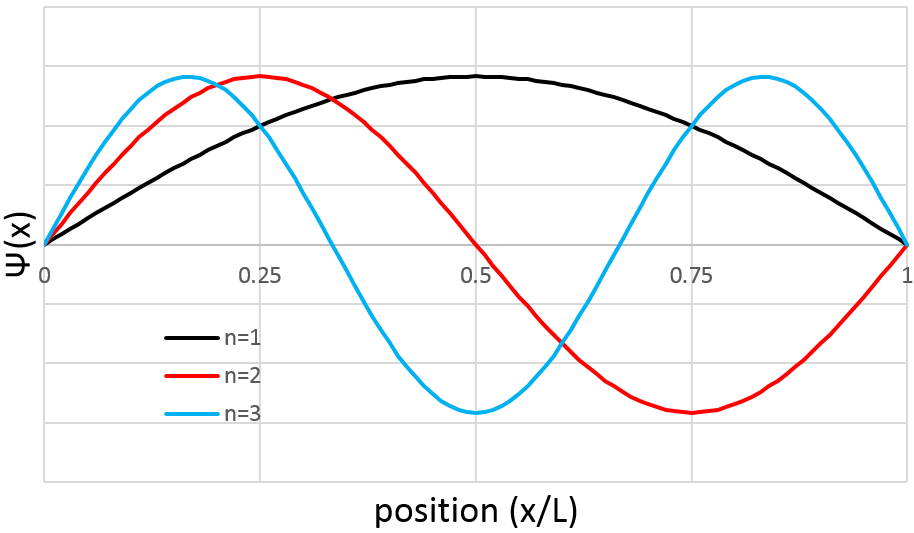

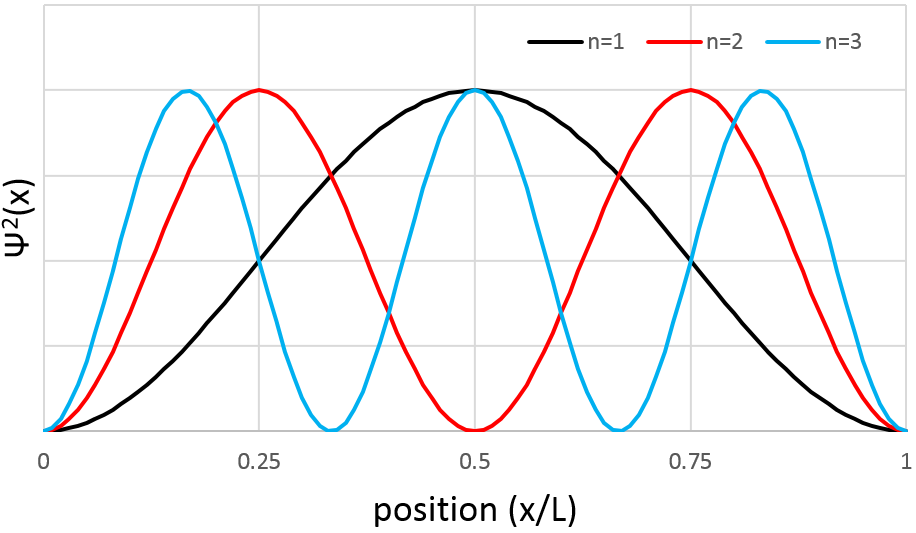

The wave has a given number n (1, 2, 3,…) of fixed points, i.e. points where the wave crosses the theoretical position of the electron on its orbital. It is easier to explain this on a linear path but it works as well on a circular orbital. This number n will be useful later.

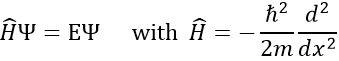

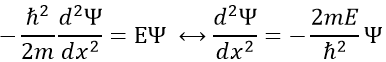

To determine the (probability of) position of an electron, we have to solve the equation of Schrödinger

Ĥ is the Hamiltonian operator and Ψ is the wave function, to be determined. To solve this equation, we use the particle in the box method: considering a square box of length L containing a particle, the probability to find the particle at a given place can be determined. In our case, the particle is an electron and the nucleus is in the centre of the box.

So, the relation to solve is

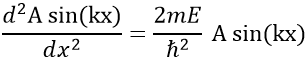

The fact that the second derivative of the function gives the function let us guess a sine or cosine function. The fact that it is negative indicates that it is a sine function. We will try a solution of the type

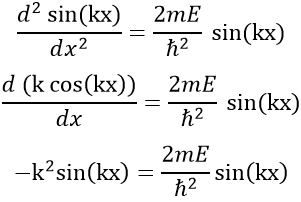

A and k will be determined later but do not depend on x. We can easily confirm our previous guess now:

As A does not depend on x, it can be placed out of the derivative without problem, and simplified with the other side of the equation

Giving us a relation for E

The values of k and of A will now be determined from the boundaries conditions of the box:

- The electron is not on the boundaries

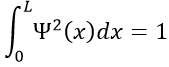

- The electron is in the box. Its probability of presence Ψ2

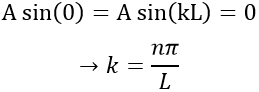

From the first relation, we find the value of k:

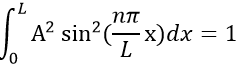

Taking this into account, the second relation gives the value of A:

The integral of the sine equals 1, so the value of A is simply

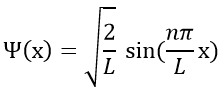

The wave function is thus

The probability to find an electron at a given place is Ψ2(x):

As a result, for n=1, the probability to find an electron is the greatest at the centre of the box, i.e. close to the nucleus. For n=2, there is a fixed point at the centre of the box, meaning that the probability to be near the nucleus is null.

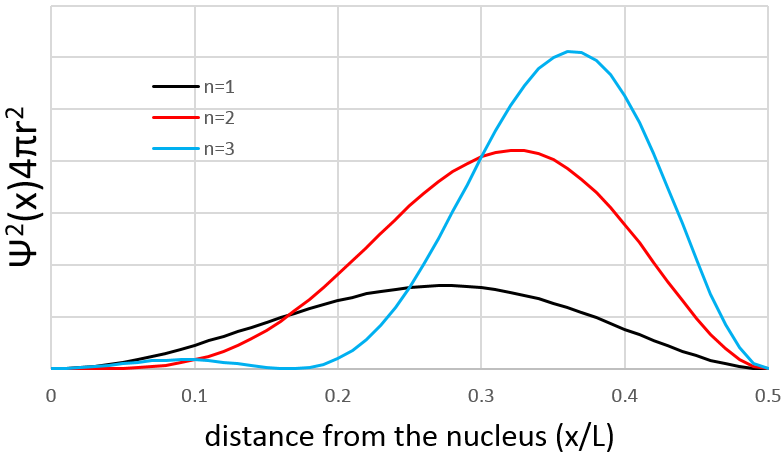

However, the volume near the nucleus is very limited and this parameter has to be taken in account. We use thus a radial probability of presence: Ψ2(x)4πr2 to obtain the distribution of electrons.

Depending on n, the (probability of) position of an electron can thus vary. For an increased n, the distance of the electrons increases but become closer and closer to each other (remember the figures of the Bohr model).

We won’t develop much more develop quantum mechanics in this section. One more notion is however needed to determine the number of electrons in the different orbitals: the quantum numbers.

Quantum numbers

There are 4 quantum numbers (QN)

- Principal QN: n=1, 2, 3,… this number defines the size and the energy of the orbital

- QN of angular moment: l.

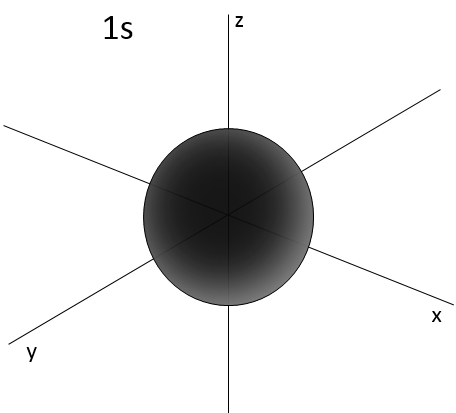

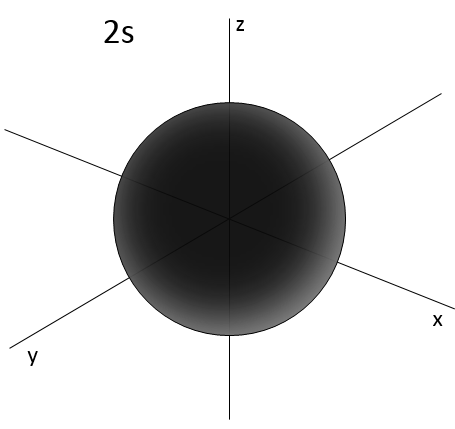

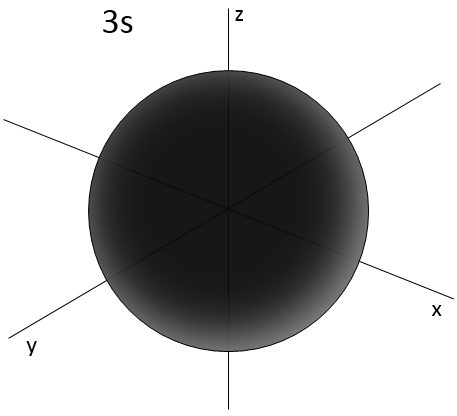

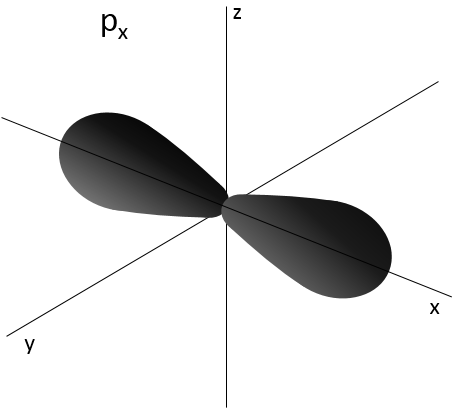

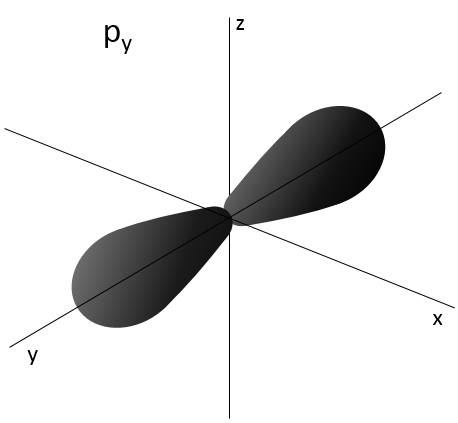

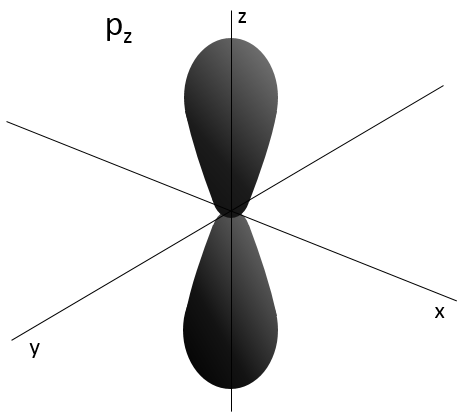

L goes from 0 to n-1. Depending on the value of l, the orbitals are named s, p, d or f. The shapes of these orbitals are different:

- Orbital s

- Orbital p

Orbitals p are axial

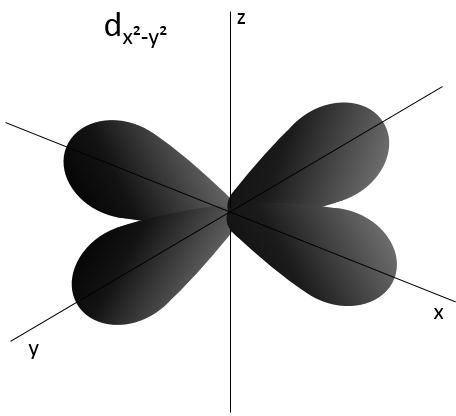

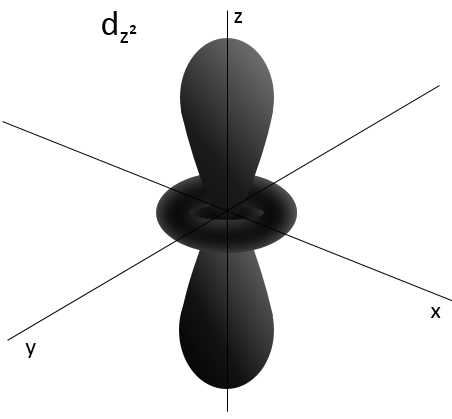

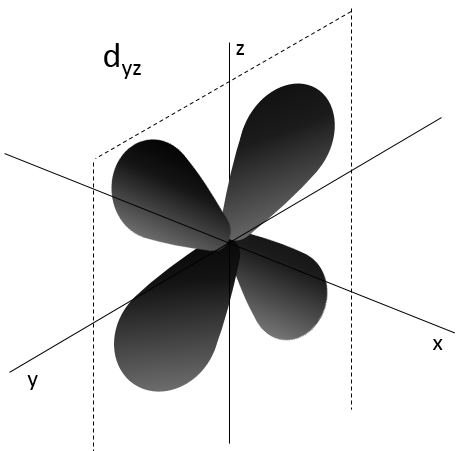

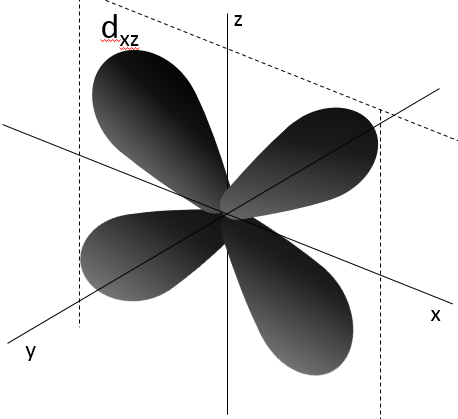

- Orbital d

Orbital d are essentially biaxial. Two of them are on the axes and the three other are at 45° between axes

- Orbital f

Orbital f are polyaxial (and won’t be drawn here, sorry)

- Magnetic QN:ml

ml goes from –l to l and defines the orientation of the orbital

- QN of spin: ms

ms defines the spin of the electrons. Electrons can go in two opposite directions and ms= -½ or ½.

Electrons must have a different set of QN: it is the Pauli’s principle of exclusion. That means that an orbital can only accept a given number of electrons. There can thus only be 2 electrons of opposite spin for a given set of the three other QN. When the two electrons are together, we said that they are paired.

For example, there can be 8 electrons for n=2: l can have a value of 0 or 1

For l=0, the corresponding orbital is the orbital 2s. ml=0 and ms can either be ½ or -½. There are thus 2 electrons of opposite spin in the 2s orbital.

For l=1, the corresponding orbital is 2p. Three ml values are possible (going from –l to l): ml=-1, ml=0 and ml=1 (corresponding in the three Cartesian directions x, y and z). Each of those can accept an electron of spin ½ and -½. The orbital 2p can thus possess 6 electrons.

In total, 8 electrons can be placed for n=2.

If n=3, 10 additional electrons can be placed in the d orbital, for a total of 18.

All the orbitals don’t have the same energy. And electrons will first take place in the lower energy orbitals. Indeed, the external electrons are on more energetic orbitals: the inner sheets of electrons are shielding the charge of the nucleus and also have a repulsion effect on the external electrons.

The energy of orbital depends on n

E(n=1)<E(n=2)<….

But also on l

Ens<Enp<End<Enf

However, the global classification is more complicated than just all the orbitals of n=1, then of n=2, etc…

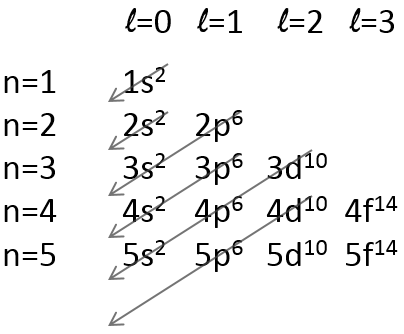

There is a method to remember the order in which we place the electrons on orbitals:

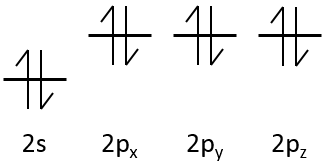

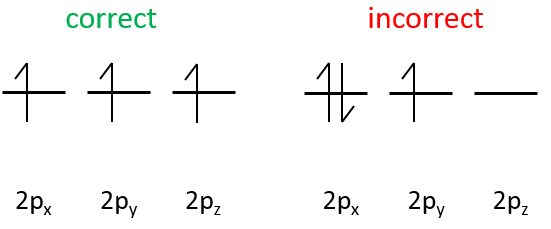

The electrons are placed following the arrows. 2 electrons can be placed on ns orbitals, 6 on np orbitals, 10 on nd orbitals and 14 on nf orbitals. This number is indicated on the figure on the top right for each set (n,l) of orbital. Two electrons are first placed on the 1s orbital, each with a different spin. The same is done in the orbital 2s. It takes less energy to place two paired electrons on the orbital 1s than one in the 1s and 2s orbitals. However in a same set of (n,l) it takes less energy to place one electron on each individual orbital. So, there are three orbitals in the 2p: 2px, 2py and 2pz. One electron is thus placed on each of those three orbitals and then electrons are paired.

There are some exceptions in this method due to the particular stability of d orbitals. d orbitals are the outer orbitals of the metallic atoms of transition. The d orbitals are very stable when they are complete or half complete, i.e. have 10 or 5 electrons. Electrons of lower orbitals can be displaced in the d orbitals to reach this quota. Let’s take a look on some metals to understand better this phenomenon.

The electronic configuration of V (Z=23) is

[Ar] 4s2 3d3

There is no need to write the complete configuration of atoms. The inner electrons don’t have any impact on the properties of the atom. Instead, we write the name of the previous noble gas between accolades. Argon (Ar) has Z=18 so there are still 5 electrons to place on orbitals. The first tow electrons are paired on the 4s and the three other are placed on 3 3d orbitals. Even if 4s has a bigger n, it is less energetic than 3d because of an effect of penetration (develop). There is nothing particular in this case.

The electronic configuration of Cr (Z=24), that has 1 more electron than V is

[Ar] 4s1 3d5

One electron has been taken from the 4s orbital to reach the half completion of the d orbitals. For Z=25 (Manganese, Mn), the 4s orbital receives the additional electron. The same phenomenon occurs for the copper Cu (Z=29) to obtain a complete 3d orbital:

Ni: [Ar] 4s2 3d8

Cu: [Ar] 4s1 3d10

On the periodic table of Mendeleev, a line begins when we place a first electron in a ns orbital. However, this is not this way that the table was developed initially. We will look closely at this table in the next chapter, explaining its shape, the elements and the general properties that can directly be related to the place of the element in the table.

Exercises

1. To which element corresponds this electronic structure:

1s2 2s2 2p4

[Ar] 4s2 3d6

[Ne] 3s1

2. What is the electronic configuration of Ar, Si, Cr, Nb, Al, F, Rb, Es?

Answers

1.

1s2 2s2 2p4 oxygen

[Ar] 4s2 3d6 Fe

[Ne] 3s1 Na

2.

Ar: [Ne] 3s2 3p6

Si: [Ne] 3s2 3p2

Cr: [Ar] 4s1 3d5

Nb: [Kr] 5s2 4d3

Al: [Ne] 3s2 3p1

F: 1s2 2s2 2p5

Rb: [Kr] 5s1

Es: [Rn] 7s2 5f11