The states of the matter

We can consider 3 different states –gas, liquid and solid– and a melange of them. One important difference between the three states of the matter is the volume they occupy. A gaz takes all the available space, a liquid takes the form of its recipient and a solid has its own form. It is the result of the interactions between the molecules composing the matter. The composition matters but it is not the single parameter to considerate. Simply set, the composition of water, ice and vapour of water is the same (H2O), but the interactions between the molecules of H2O are different. Sometimes things are not totally a solid nor a liquid nor a gas. An example is the shaving foam: it has not its own shape but does not completely take the shape of its recipient. Generally, in this case we are in presence of a melange of two cohabitating states. The goal of this chapter is to describe the different states of the matter and the transitions between them.

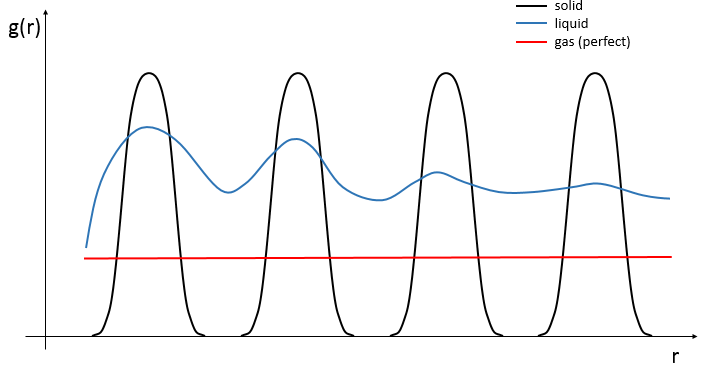

The arrangement of the matter can be defined from the repartition of neighbour atoms between them. If we focus on one specific atom, the probability g(r) to find one or many atoms at a given distance r of the atom differs strongly between liquids, solids and gases.

In a solid, the atoms are organised and don’t move freely (they can vibrate around their position). The repartition depends on the geometry of the solid but it is characterised by high, localized peaks at regular distances with g(r)»0 between them. In a liquid, we can see that there are still layers of neighbours around a given atom but that the order is less important. Moreover, the peaks vanishes after a few layers. A liquid is thus characterised by a short range order and disorder at long range. The average number of neighbours in a liquid is in general smaller than in a solid. In a perfect gas, the atoms don’t feel each other and have no interaction. The probability to find an atom at a given distance of another one is thus equal at any distance. In real gas however, interactions can exist and g(r) varies slightly.

Gases

We are surrounded by gases. We can displace them when we are moving but they apply a resistance to our moves. Even when we are not moving, there is a pressure of the air on us. We don’t feel it because we are used to it and our body applies a force to counter this pressure. If the void was made, we would expand because of this force. The fact that air applies a pressure has been proved by Otto Von Guericke (XVIIth century). He build two half spheres, fitting each other. He removed the air from them and asked to his lord to try to open it with the help of four horses. They did not success. Putting back air into the sphere, it was possible to open it again.

There are still objects that we often use based on this principle: suction pads for plumbing, the ones to put your GPS on the windscreen. The void that we create is never complete and the strength necessary to remove a suction pad depends on the degree of void that we created. It becomes way easier to remove them once we allowed a bit of air to get in the suction pad.

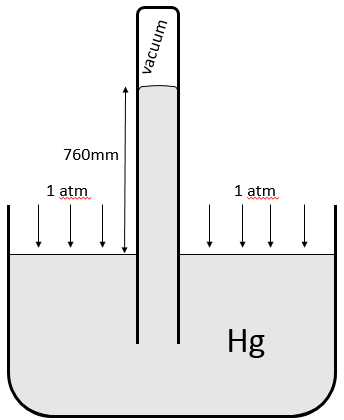

A pressure is a force applied on a surface. The pressure applied by the air in standard conditions is 1 atmosphere, which equals 101325 Pascals, more usually given in hectoPascals (1013hPa). We also measures the pressure of a gas with torr. 1 atm=760torr. The torr unit is the height, in mm, that mercury reaches in a voided tube when a pressure is applied on the rest of its surface in the following disposition.

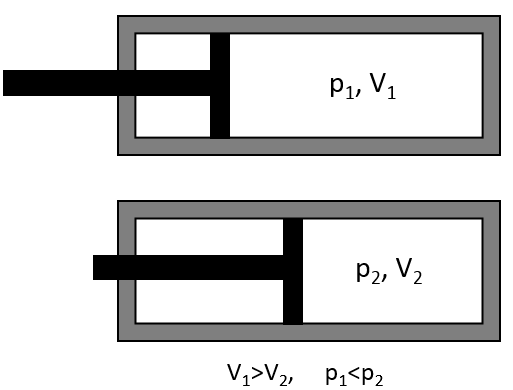

There is a relation between the volume of a gas and its pressure. Boyle determined that at a constant temperature, the multiplication of the pressure of a gas by its volume gives a constant.

If the volume decreases, the pressure increases by the same ratio:

Charles Gay Lussac observed on the other hand that the volume of gas depends on the temperature and that, does not matter the gas, its volume trends to 0 when the temperature goes towards 0K (he extended the curves when the gas changes of state).

A third contributor to the understanding of the gases is Avogadro who said that at a given temperature and pressure, the volume of a gas is proportional to the number of atoms it contains:

k is the constant of Boltzmann. Considering all of that, the law of perfect gases was established:

This law is limited to diluted gases and we consider that the particles are punctual, distant and that there is no interaction between them.

If we consider several gases, Dalton showed that the total pressure is given by the sum of their individual pressures.

![]()

As a consequence, if we consider a melange of two gases

![]()

The individual pressure of one component of the gas is proportional to its concentration in the gas:

![]()

Kinetic theory of gases

We can measure the pressure applied by a gas on a surface. As explained before, a pressure is a force applied on a surface. A force is a mass multiplied by an acceleration. An acceleration is the variation of speed over a time.

Note that only the component of the speed perpendicular to the surface affects the pressure. The two other components don’t have an influence on this particular surface.

We make several assumptions about the particles of the gas:

- The particles are small and their volume is negligible compared to the volume of the gas. They are considered as dots.

- They all have the same mass m,

- They have a constant speed and go in random directions. We can define an average speed <v>.

- The particles don’t interact together

- All the collisions are purely elastic: there is no loss of speed or energy

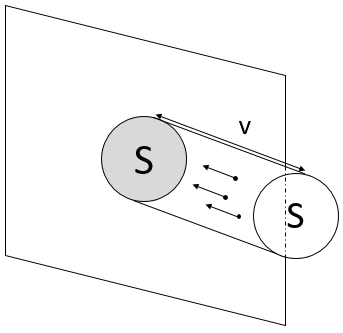

To determine the pressure on a surface S of one of the walls, we consider the particles that are able to hit this surface in a period of time dt. As a result, we only consider the particle present in a small cylinder in front of the surface.

When a particle hits the wall, there is an elastic collision and the particles goes back with the same speed. Over one period of time, the speed of a particles changes from v to –v. The force applied on the surface by one particle is thus

![]()

In the cylinder, there is a given number of particles:

N/V is the density of particle in the gas. Amongst them, only the particles going in the x direction are important for us, and amongst them only the particles going in the direction of the surface (not in the opposite direction) induce a pressure on the surface. A 1/6 multiplication is thus applied to determine the number of particles impacting the surface. The pressure is thus

![]()

In this equation, we recognise the kinetic energy Ek=mv2/2. Keeping in mind that N=n.NA, we can write

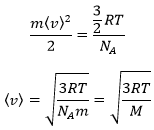

As a result, we see that the kinetic energy of particles in a gas is directly proportional to the temperature

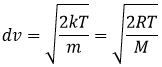

From there, we also see that the average speed of the particles is related to their mass:

It means that in a gas at a given temperature, particles of oxygen and of nitrogen do not move at the same speed. For example, a balloon of nitrogen (N2, M=28) deflates faster than a balloon full of oxygen (O2, M=32)

This property is used to enrich uranium, i.e. obtain a larger proportion of one isotope of the uranium. Considering a volume of gas containing 235UF6 and 238UF6, a bigger proportion of 235UF6 will pass through a small gap because it has a larger speed than 238UF6. This process is the effusion: a separation based on the speed of the particles.

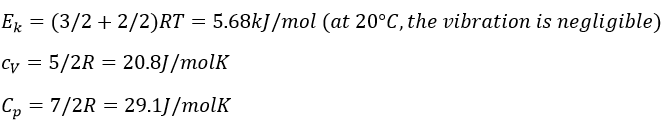

The heat capacity (at V=cst) is the energy required to increase the temperature of one mole of gas by 1° is

The heat capacity (at p=cst) is

In a monoatomic gas, all the energy is used to increase the speed of the particles.

Diatomic gases

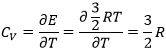

For molecules of more than one atom, the kinetic energy is split up in the three directions (1/2R by direction).

If a diatomic gas is heated, the energy is used by several processes:

- translation/acceleration: the speed/kinetic energy of the molecule increases,

- rotation and vibration

There are two angles of rotation, the energy required to rotate is 2*1/2R

If the molecules vibes, they have a potential energy. The energy obtained from the heating is thus distributed in kinetic energy and in potential energy. The energy required to vibe is thus also 2*1/2R.

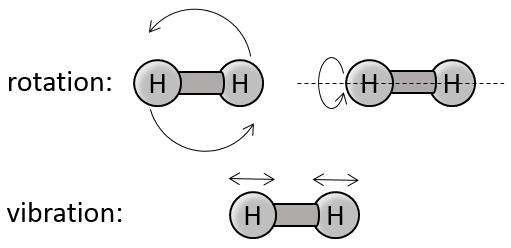

The values of Cv and Cp are thus higher than for a monoatomic gas:

So, if we give energy to Ne and N2, which gas should heat more? N2 uses the energy of the heating to accelerate but also to vibe and to rotate. Ne uses all the energy as kinetic energy and will thus heat more than N2.

Distribution of Maxwell-Boltzmann

The calculations we have done assumed that all the particles of a gas were affected identically by the heat. In reality, the heat capacity depends on the temperature but trends to 7/2R for T trending to infinite. The explanation follows:

Particles can have different levels of kinetic energy. When energy is supplied, not all the particles are equally excited. One proportion of their population increases its kinetic energy by one level (or more eventually). At OK (absolute zero), all the particles are at the lowest level and don’t move. They are frozen.

The population on the second level is given by

ΔE1 is the difference of energy between the level 1 and the level 0. k=R/NA is the Boltzmann’s constant. In general, the population is given by

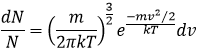

The distribution of speed of the particles in the levels of energy are given by the law of distribution of Maxwell-Boltzmann. From above, we can determine that the variation of level with regard of the variation of speed

With A an undetermined constant. We can write this equation differently:

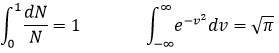

It is possible to integer this equation, knowing that

It would mean that A=(m/2πkT)1/2. However, the speed has three components. As a result, the distribution is

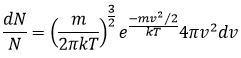

Similarly to the probability of presence of the electrons for the electronic orbitals, we integer on a sphere and we should multiply this equation by 4πv2. We have thus obtained the proportion of particles dN on the total number of particles N with a given speed dv.

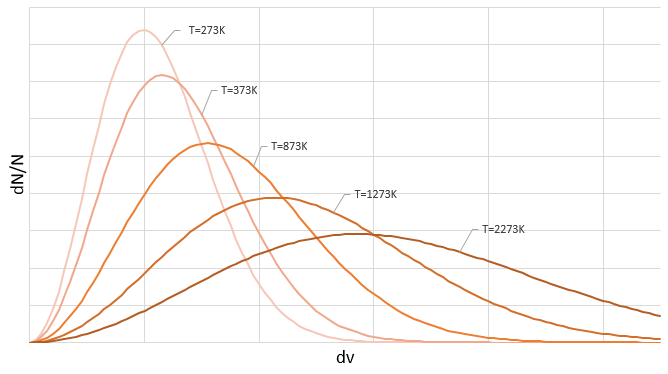

One can see on this figure that the average speed increases with the temperature, as it was determined previously in the relation

from the law of perfect gases. The most probable speed is found at the maximum of the curves, when dN/N/dv=0, i.e. at

The average speed that we find is a bit smaller than the one obtained from the law of perfect gases:

Real gases

The law of perfect gases works well for diluted gases. If we increase the pressure or the temperature of gases, we see deviations from the law of perfect gases.

It is because the number of interactions between the particles becomes less negligible. The interactions can be attractive or repulsive but are weak with regards to the energy of a liaison for example. The interactions can be between induced dipoles or between permanent dipoles:

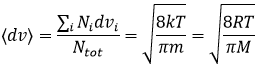

Interaction permanent dipole-permanent dipole

In this case, the molecules composing the gas already possess a dipolar moment. The δ+ and δ- charges of molecules passing near each other interact: an attraction is induced between opposite charges and repulsion between dipoles of same charge.

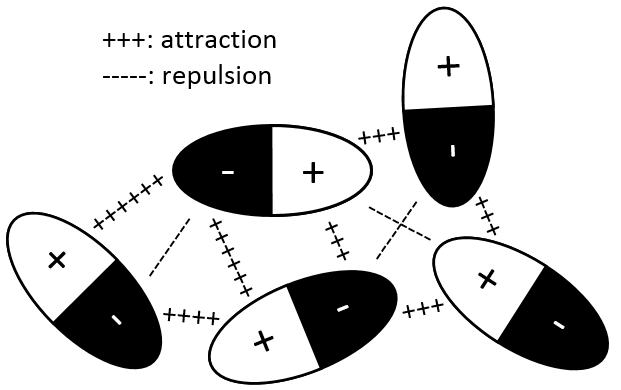

Interaction induced dipole-induced dipole

The electrons near a nucleus are, statistically, equally distributed around the nucleus. In other words, the cloud of electrons is spherical and the density of electrons is identical in all the directions. However, the electrons are continuously moving and heterogeneities of charge may appear temporarily. In fact the apparition of these dipoles is frequent but in average the dipolar moment is cancelled.

When an atom passes near another atom showing a dipole, the atom adapts its electrons cloud to the dipole to reduce the repulsion between them.

In general, the interactions are favourable between the particles of a gas. The particles tend to remain close of each other, decreasing the pressure with regard of a perfect gas.

On the other hand, the particles have a proper volume and the other particles cannot penetrate this volume. In the law of perfect gases, the particles were considered as dots, with a negligible volume.

As a result, despite the increase of interactions, the pressure increases faster than for a perfect gas.

Instead of the perfect gas law PV=nRT, we have to consider the van der Waals equation for real gases:

In the pressure term, the +a(n/v)^2 expresses the interactions between the particles. a stands for the interaction strength, the value of which depends on the type of interactions, the size of the molecules, the number of electrons, etc. (n/V)^2 stands for the “density” of interactions and should in fact be n/V*(N-1/V) as each particle of the volume (n) can interact with all the other particles (n-1) but as n is proportional to NA, the difference is negligible.

In the volume term, b stands for the covolume of one particle. The empty volume where particles can move is the total volume minus the volume of the n particles composing the gas.

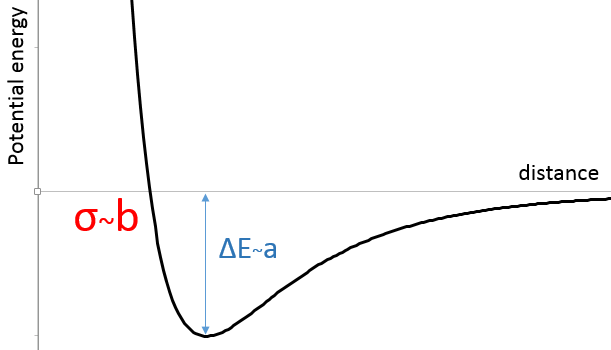

In the figure of the potential of Lenard Jones, we can relate a and b to the energy of the pit and to the distance of smaller approach σ.

The enthalpy of vaporisation ΔHv reflect the energy required to transform a liquid into a gas. It requires more energy to vaporise molecules with strong interactions than molecules with only induced dipoles. Sprays of water are sold because of this property: once on our skin, the small droplets vaporise, taking the energy from the skin, decreasing its temperature and giving a feeling of freshness.

The opposite process is the liquefaction. The molecules in the gas are distant from each other. To become liquid, the particles move into the potential pit. However if they have a too large kinetic energy (depends on the temperature), they will get away from the other particle. It takes energy to leave the potential pit. As a result, liquefaction involves a decrease of the temperature.

Exercises

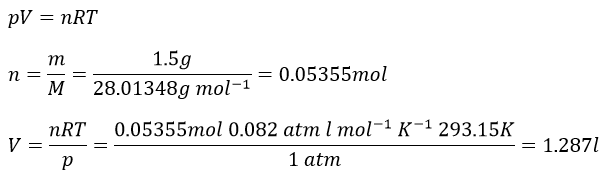

1. What is the volume of 1,5g of N2 under a pressure of 1atm, at 20°C?

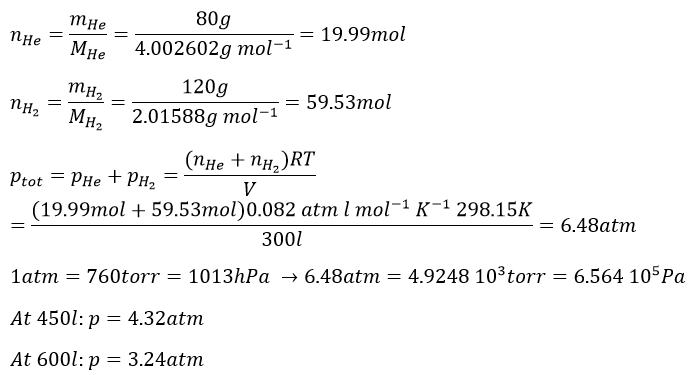

2. What is the total pressure of a gas composed of 120g of H2 and of 80g of He if the temperature is 25°C and the volume is 300l? Express your answer in atm, Pa and torr. What in a volume of 450l or 600l?

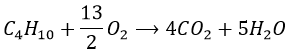

3. What is the required volume of oxygen to burn 1g of butane (C4H10)? Knowing that all the products are gaseous, what will be the volume after the complete combustion?

4. Considering that the combustion of 1g of a gas composed of CH4 and C2H6 formed 1568ml of CO2 and water at 18°C and 742torr, what are the masses of CH4 and C2H6 of the sample?

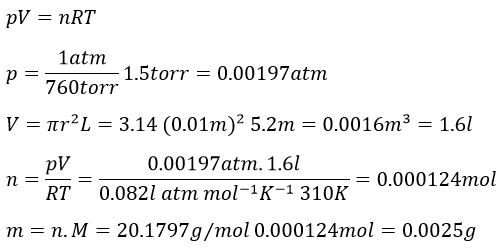

5. To produce a neon lamp of 520cm long by 2cm of diameter, the pressure inside the tube has to be equal to 1.5mm Hg at 37°C. Determine the mass of neon required to obtain those conditions.

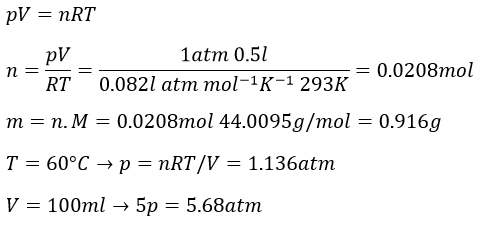

6. A recipient of 500ml is filled with CO2(g) at the pressure of 1 atm at 20°C. What is the mass of the gas? What is the pressure if we increase the temperature by 40K? What is the pressure if we next compress the gas to a volume of 100ml?

7. Sort the following systems from the closest to the farthest of a perfect gas:

a)H2 at SCTP

b)He at 350K and 1 atm

c)H2 at 273K and 2 atm

d)He at SCTP?

8. Compare the results of the equations of the perfect gases and of Van der Waals (a=4.17l2/mol2, b= 0.0371l/mol) for a volume of 20l, 2l and 0.2l containing 1 mol of NH3 at 0°C.

9. Considering that the minimum of the function of Lennard-Jones for the argon is at -996J/mol at a distance of 0.382nm between the atoms, what would be the potential at a distance of 1/2×0.382nm, 2×0.382nm and 3×0.382nm?

10. What is the kinetic energy of 1 mol of Ne at 20°C and 1 atm. What are its heat capacity at a constant pressure and at a constant volume? What is the difference if instead of neon we had nitrogen?

Answers

1. We use the law of perfect gases to solve this problem

2.

3. The first step is to determine how many moles is 1g of butane:

Now we write the chemical reaction to find the stoichiometric coefficients

The required volume of oxygen is thus

9 moles of gas are produced by the reaction per mole of butane, so the volume after the reaction is

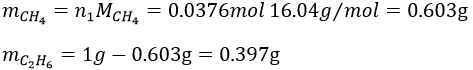

4. The reactions of combustion are

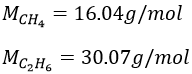

We know that 1g of reactants give 1568ml of CO2. The molar masses of the reactants are

In 1g we have n1 moles of CH4 and n2 moles of C2H6

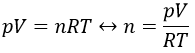

As we have the volume, the pressure and the temperature of the CO2, we can determine how many moles of CO2 are produced by the reaction with the law of perfect gases

The pressure has to be put in the IUPAC units (atm) instead of torr: 1atm=760torrà 740torr=0.974atm and the temperature is put in Kelvin (°C+273.15)

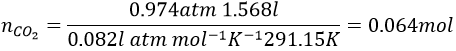

1 mol of CO2 is produced for each reaction of combustion of CH4 and 2 are produced by each reaction of C2H6. The total amount of CO2 is thus equal to

We have two equations with two unknowns to solve. To do so, we can insert the expression of x into the first equation

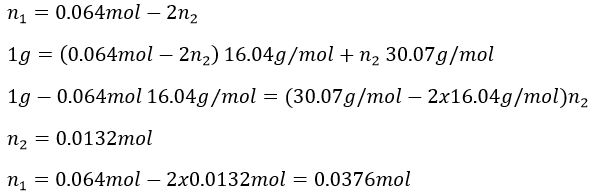

The masses are thus

5.

6.

7. b-d-a-c

8.

9.

Diatomic gas: